Fokus

Ars totum requirit hominem

Essays

14.01.2022

On the art synthesis installation “A galaksija okolo sija” (And the galaxy shines around) by Vladan Radovanović, on the occasion of his receipt of Politika Award for the best exhibition in 2021.

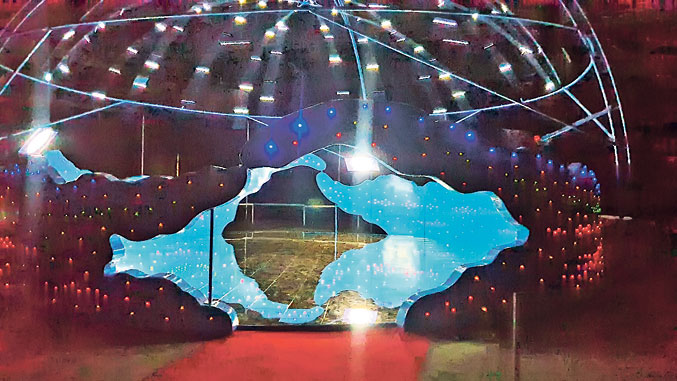

Warmest congratulations to our artist Vladan Radovanović (1932), on winning the prestigious Politika Award for the best exhibition in 2021 with his immersive art synthesis piece, A galaksija okolo sija (And the galaxy shines around), exhibited at Hall 4 of Belgrade Fair in September 2021. The award was granted by the jury consisting of: Ljiljana Ćinkul, art historian and Politika’s art critic, Simona Čupić, professor of Art History at the Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade, Svetlana Mitić, the curator at the Museum of contemporary art in Belgrade, Saša Janjić, independent curator and Marija Đorđević, the editor of the Culture supplement of Politika. The realisation of A galaksija okolo sija (AGOS in further text) has been supported by Wiener Staedtische and Wiener Art Collection.

Text by Alexandra Lazar

AGOS is Radovanović’s Sistine Chapel: the spectacular concept, the scale of the work, the years of commitment and lengthy process of realisation, the look into the micro and macro plans of creation and history, the playful use of all senses. Even its initialism, AGOS, has meaning: in Greek: ἄγος is ”abomination”. It could also be a very big baby mobile, twinkling away with moons and stars above a cradle. So which is it? While the press auto-reflexively published only the descriptions of the interactive components of the work and the artists’ statement about his poetics and the art synthesis, highlighting it as the crowning piece of his 70-year career (which it arguably is), we should look at AGOS as a piece of its times, a work that communicates its author’s ideas of the world reachable by our senses. Are artworks such as this transforming our idea of history, the universe, or of how either of them communicates? Is it transforming our idea of art, or what art can tell or show us?

Radovanović’s AGOS is a product of a singular artistic vision, thus not necessarily concerned by science or universal facts. However, it uses the mathematical model of the universe, as well as the mythical symbolism of the world reflected on its axis, as a starting point upon which he builds his immersive space. Of course, he’s not the first to do so: ever since Galileo published his drawings of the moon in 1610, astronomy has aided artistic vision and depth of enquiry. With the invention of the Hubble telescope came a newfound sense of the enormity of space and the smallness of ourselves. It is a beautiful and humbling thought. With the climate change engulfing our planet, we have bigger concepts and solutions to grapple with at our doorstep. So how can AGOS be seen as novel, revolutionary or even contemporary?

For the centuries that science and religion alike considered our planet to be the centre of the Universe, the solar system a mere decoration playing in the background of our earthly fates, artists’ singular centrism served not only to present and make sense of the unknowable expanse of the space, but also as a metaphor or archetype depicting their inner world. Artists described the ephemerality and resilience of nature and the endless fascination with the cosmos, enmeshed with the ideas of time, language, complexity that reflect the artist’s era and personal philosophy.

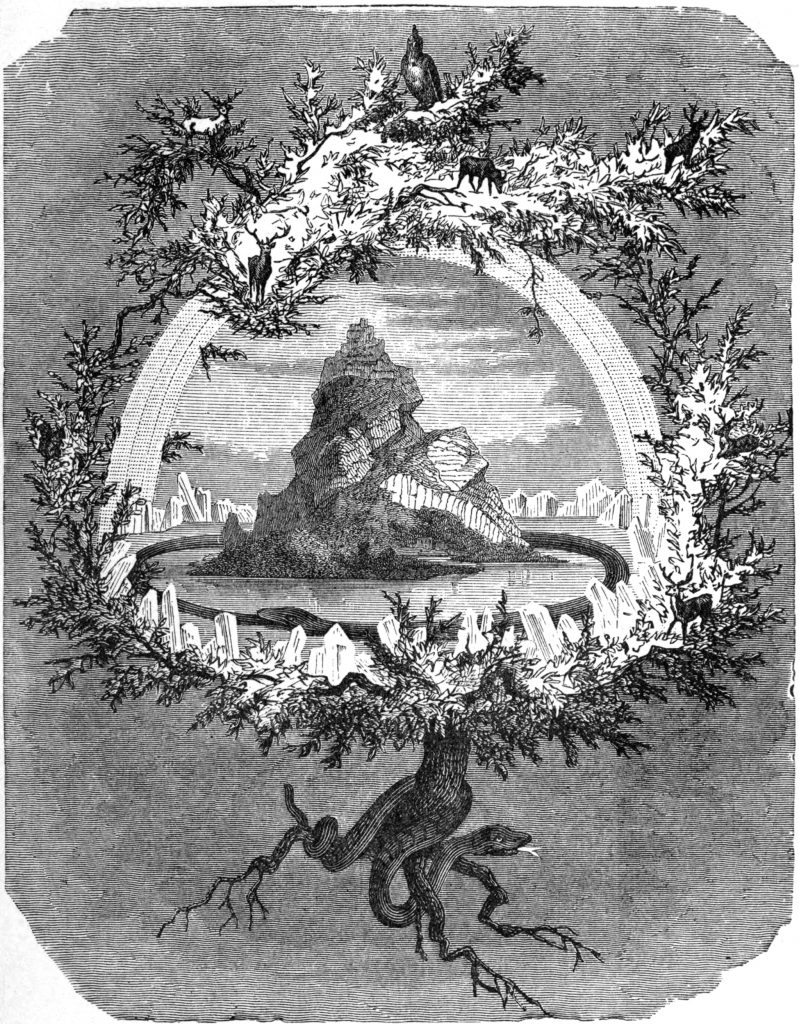

AGOS does just that. It provides an entry into a personal universe, which uses multisensory components to paint a three-dimensional kinetic scene, with the viewer as its crucial energetic component. Hence Ars totum requirit hominem from the title — art requires a whole (hu)man, an entire being from both the creator and the viewer. The central forum of his space is a semi-sphere reflected in a mirror, like a three-dimensional Yggdrasil, which represents the link between the universes. The reversal and polarity of meaning, present in many other folklore, alchemical or religious representations, is also present in the form of words and images that on reflection reveal their opposite. The gap between major and minor keys in this thus presented history of the universe (Big Bang was a global event; Bill Klinton playing saxophone while OV-1 Mohawks deliver fire to their targets in Serbia was comparatively local) is intentionally left agape for the viewer’s own analysis.

The sphere can also be seen as a three-dimensional mandala, akin to K.G. Jung’s vision of a World Clock which he formulated in 1934, and which theoretical physicists subsequently accepted as the archetype of quantum consciousness. [i] This vision of unus mundus (unified world) represents a union of opposites that transcends the artificial separation of the psyche and matter and, by definition of art synthesis, of cognition, creation and senses. This idea of completeness, wholeness, ars totus (total art) and hence homo totus (total man) speaks of Radovanović’s desire to navigate the labyrinthine earthly roads, signs and obstructions towards a harmonious higher self. AGOS may be seen as a place for alchemical transformation where the viewer, in the tradition of early Egyptian, Hellenistic or mediaeval gnosis, stands at the core surrounded by the four elements, like the ancient Thoth, Hermes Trismesgistos or Christ Anthropos. The spectre of colour, according to Rosarium philosophorum, symbolises lapis philosophum, the philosopher’s stone that unites all colours within itself (“lapis noster est ex quatuor elementis”), and the four colours of the elements represent the creation of the Anthropos, the human being. [ii] The ‘abomination’ from the artwork’s titular initialism may present a warning, although I wouldn’t ascribe the author any prescriptive moral stand.

It is therefore not a huge leap to propose that the artist’s work with concepts and senses is in fact an alchemical synthesis of prime elements, a magical arcana powered by his imagination and dedicated to a Creator of the Universe, whoever they may be. I am also interested to note the parallel between Radovanović’s art synthesis and Pauli-Jung conjecture, acausal parallelism that is “the meaningful coincidence of two or more events where something other than the probability of chance is involved”, and where chance fluctuations of viewers’ internal and external responses to the interactive piece by the means of touch, movement, cognition and interaction complete, orchestrate and fulfill the constellation of the artwork. It is precisely this purpose-seeking synchronicity — K.G. Jung’s Synchronizitát — that creates life within Radovanović’s Galaxy. [iii]

Whereas at times it may feel like the artist has bitten off too much – if indeed his interest was mnemorphosis that would expand the space between the physical and virtual worlds via the limited means of language, image, sound, movement and technology – the work sits well within the contemporary poetics situated within current questions of posthumanism. It seems fitting to have a ticking clock of the Anthropos as the symbol of the anthropocene. We have indeed reached the limits of our world; but possibly not the limits of consciousness.

Is it transforming our idea of history? Sadly, we live in the era that seems to cloud and relativise even the simplest ethical decisions. Can we agree on the artistic merit of AGOS? What does it mean to us? This question brings to mind two much older artworks, Giovanni di Paolo’s (1403–1482) The Creation of the World and The Expulsion from Paradise (1445), and Hildegard von Bingen’s Macrocosmos created in image of a man (Liber divinorum operum, XII A.D.), ancient data visualisations that interrogate our place in the universe, asking us to make an informed and ethical choice of our own.

Within the spectrum of artworks that addressed individual’s idea of the Universe, I am reminded of Diego Rivera’s mural created at the Rockerfeller Centre in New York in 1933 under the title Man at the Crossroads, and remade a year later at the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City under the name Man, Controller of the Universe. Both versions depict a worker at the centre directing an enormous machine at the crossroads of the political ideologies dominating this period: the right wing, The Frontier of Material Development, represents capitalism, whereas the left, The Frontier of Ethical Evolution, represents communism. The artist’s critique of capitalism and traditional art history proved to be unpalatable for the Rockerfellers, who destroyed the original after Rivera refused to remove the figure of Lenin; the artist responded by recreating it anew in Mexico City, adding further political figures and allegories.

Rivera’s critique of the political and cultural elite that had repressed masses throughout human history is not too far from Radovanović’s concern that the acts of the Yellow House or the bombing of Serbia may be forgotten – these are personal, individual, sometimes problematic keyframes that may or may not survive the course of history, but that should not be censored or polished away for a more universal appeal. The process of keyframing – highlighting one event in the timeline as more important than others – is after all irrepressibly individual, be it imbuing deeper meaning to celestial charts, or isolating particular moments in history of the universe to orchestrate an artistic vision. This can be contrasted with the installation Totality (2016) by the Scottish artist Katie Patterson, who created a mirrored ball depicting every solar eclipse ever documented, from centuries-old drawings to the most recent documents. Patterson choose a key event which, although deeply poignant, bears noe motional weight for most veiwers, and this apparent neutrality gives the work its calm, aesthetized aura. That is not to say that the lack of involvement is in any way artistically superior to Radovanovic or Rivera. The viewer that enters Totality can’t add or substract anything at all, becoming themselves a speck of light reflected on the wall.

This ahistorical neutrality, the impossibillity to rouse personal empathy for the event that is unknowable to us, leads to other contemporary immersive spaces depicting artists’ personal vision of the universe: Yayoi Kusama ’s Infinity Rooms, Ryoji Ikeda’s Dataverse or Zhan Weng’s My Personal Universe. All three observe or represent a universe, and all have their own personal and artistic meaning, but all of these works remain ideologically ahistorical.

When Yayoi Kusama created her first Infinity room, Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field in 1965, Kusama translated the painterly repetition to three-dimensional space in order to displace the viewer: in a way the opposite of Radovanovic’s ticking clock, bookended by the Big Bang and the end of the known universe, Kusama’s fields are kaleidoscopic environments that deceive the viewer with an illusion of timelessness. Moreover, the only interactive part in My Personal Universe or Infinity Rooms is our movement through them: we have no agency in this world. Within this relational field the viewer senses that their pesonal reactions may be entirely pointless; the artist’s decision to render the veiwer helpless and hopeless about their place in the world is inescapeably ideological, just like the bourgeois art criticised by Diego Rivera.

Dataverse (2019) by the electronic composer and visual artist Ryoji Ikeda touches upon the immeasurable expanse of facts: open source scientific data sets from various institutions such as CERN, NASA, and the human genome project were processed, converted and orchestrated to visualise and sonify the vast number of dimensions co-existing in our world. Ikeda calls it “data visualisation as a burst of transcendent information exchange”, but again, the viewer is not a participant nor creator. While structurally complex, Ikeda’s Dataverse is interested in the universality and transparency of art (be it mathematics or music), while concerning himself with the universal values.

While technically and technologically immense, these recent artspaces are examples of materiology — the constellations of objects and the fabric of art — which do not attempt to trespass into the shady world beyond science or cognition. Using light to illuminate that which is known, as opposed that which is hidden, seems satiated with the pleasing aestheticised spectacle.

AGOS, in comparison, is a mobile and partially scripted tableau within which the viewer can act (albeit in limited and prescribed ways), and which can be understood as the artist’s way of engaging with the suppressed as well as the exposed, known as well as unknowable. It may be limited, but it cultivates agency. While we may never be certain if Radovanovic’s galaxy is truly intended as an ambient of creative initiation of the viewer or just a space with which to further experiment with the conceptual premises of the art synthesis, it offers a complex spectrum of dualisms at the end of duality, a strikingly retro modernist auteur vision, and an expressive capacity of Gesamtkunstwerk rarely seen in our times.

Footnotes:

[i] World clock is a vision of multidimensional universe, from a dream by physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who discussed it in detail with K.G. Jung. Unlike Jung, who considered the collective unconscious as “objective” and prior to our individual experience, and acting as a source of imagination and creative work, Pauli favoured the thesis that creative ideas are formed through a correspondence between the outer reality and archetypal images. Jung and Pauli modelled a seven-dimensional space-time, seven-dimensional structure of the physical world, which suggested an implicit order behind quantum physics, the unified psychophysical reality, unus mundus. Described in detail in K.G. Jung’s Psychology and Alchemy, and in later personal correspondence between Jung and Pauli (1952) on Bohm’s theory of quantum physics and Bohr’s complementarity of particle and wave.

[ii] De Alchemia, Nuerenburg 1541. and Tractatus aureus de lapidis physici secreto, attributed to Hermes Trismesgistus but probably an older Arabic text. Biblioteca chemica curiosa, Vol. II, ed. Johannes Jacobus Mangetus, Geneva, 1702.

[iii] See more about K. G. Jung and W. Pauli’s Sinchronicity here.